023. Joni Mitchell, MFK Fisher and Jaco Pastorius

feat Penguin Guide selection Jaco Pastorius (recorded 1975)

“Raised on Robbery”

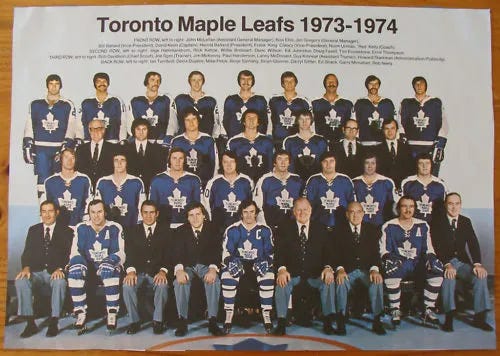

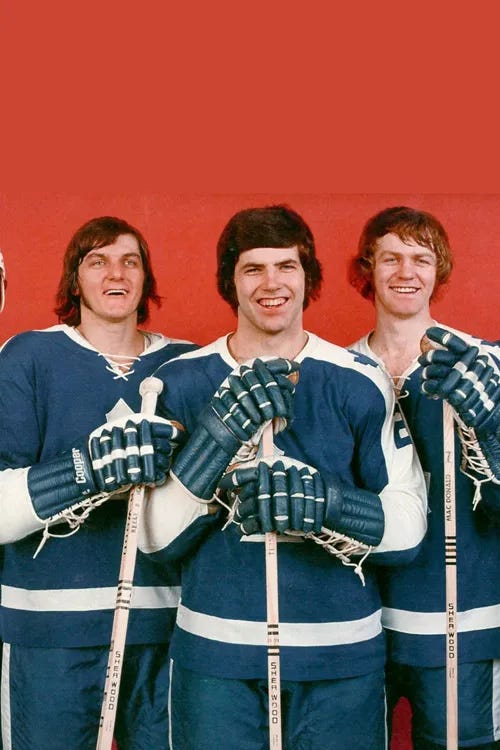

It started last Monday, a dreary cold April day in Toronto. I’d just dropped my kids off at school. Since the move, I drive them to school every day now, instead of walk. I was feeling particularly melancholy and threw on Joni Mitchell’s 1974 classic, Court and Spark. The mood of the title track hit perfectly as I meandered through mid town Toronto streets. I toggled through a few tracks, landing on “Raised on Robbery,” mostly because it featured the Toronto Maple Leafs just as the team is gearing up for the playoffs.

He was sitting in the lounge of the Empire Hotel

He was drinking for diversion

He was thinking for himself

A little money riding on the Maple Leafs

Along comes a lady in lacy sleeves

The song bridges the gap between sex workers and finance bros, framing the interaction in a playful and wry way that helps give the cold, stodgy male energy of the corporate Leafs season-seat holder some vibrancy and sense of humour.

Joni fan debate rages as to the location of the actual Empire Hotel Joni is referring to. Saskatoon? Regina? Huntsville? No matter. I’m imagining the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1974, when Court and Spark was released. Only seven years removed from their last Stanley Cup. Ah, what a time.

Fast forward to today, where Toronto has the longest championship draught in the league at 58 years. I’ll watch the playoffs, as we take on the Ottawa Senators in the “Battle of Ontario” projected to start this Sunday, April 20. I can imagine Robbie Robertson’s opening electric guitar lick chopped and screwed for the PA system at Scotiabank Arena.

Hejira

I’ve listened to the Court and Spark album through and through enough times to warrant a need for a fresh Joni Mitchell lens to view the world through. I’d received a digital copy of her 1976 Hejira album from a friend while living at a hostel in Buenos Aires in 2011. I hadn’t given the album a fair shot until this past week. Not only did the album serve as a road weary companion to a wintry April stint, but it introduced me to Joni’s jazz period, where she enlisted some of the best jazz players of the day to play on Hejira, including fretless bass virtuoso Jaco Pastorius, who has a four-starred album in the Penguin Guide to Jazz.

Joni’s website is a treasure trove of historical written archive. Wally Breese writes about the meeting of Joni and Jaco in “Biography: 1976-1977 Refuge of the Roads.”1

Joni recorded HEJIRA in the summer of 1976, with many of the same musicians she'd used since 1973, but the sound she wanted this time was more subdued and moody. She wanted music that echoed the sounds of the road songs she'd written. Many of the songs on the album dealt with learning to be at peace with not having a family…

When she'd completed recording the 9 tracks that comprise the HEJIRA album, she was told by a friend about a bass player she should hear who was creating a ruckus with his unusual playing style. Joni met Jaco Pastorious and immediately connected with the way he played his bass. John Guerin told Joni, "God, you must love this guy, he almost never plays the root!" Joni had been trying for years to find a certain sound on the bottom end of the bass, and Jaco's playing was a dream come true for her music. She overdubbed his bass parts on 4 of the songs on HEJIRA, and the album was readied for release in late November…

In an article that originally appeared in the first edition of the Ultimate Music Guide published in May, 2017, Laura Snapes profiles every Joni Mitchell album, including Hejira :

… by the mid-'70s, Mitchell was keenly following Marvin Gaye in "moving away from the hit department, to the art department", keen to forge her own rhythms away from rock. In the wake of her split from drummer John Guerin, she was ready to give life the slip for a while.

After the end of the Hissing tour, Mitchell was sojourning at Neil Young's beach house. She wanted to travel, but didn't know where, or who with. By chance, two friends invited her to drive cross-country. Her answer: '"I've been waiting for you; I'm gone,"' she recounted to Rolling Stone's Cameron Crowe. They travelled together for a while before Mitchell went off alone. It was one of three road trips she took between 1975 and 1976, which led her from Los Angeles to Maine, then California via Florida and the Gulf Of Mexico. On the road, Mitchell stayed in lighthouses along the Gulf Coast and wore wigs to disguise herself in New Orleans. "Meanwhile, nobody knew where I was," she told White. "I'd do those disappearing acts. I'd pass through some seedy town with a pinball arcade, fall in with people who worked on the machines, people staying alive shoplifting, whatever. They don't know who you are: 'Why you driving that white Mercedes? Oh, you're driving it across country for somebody else.' You know, make up some name and hang out. Great experiences, almost like the prince and the pauper."

Mitchell had no license for her flashy car, so she drove behind truckers, who would signal when the police were approaching. She was living out of bounds, but hadn't, as the folk song goes "fallen by the wayside". By the mid-'70s, Walden and On The Road were archetypal male quests, but there were still few cultural precedents for women travelling alone. Eighteenth-century "girl stunt reporter" Nellie Bly circled the world in 72 days to prove that she could. Simone De Beauvoir's America Day By Day (1947) was more journalistic, intended to convey the reality of America's culture and mores to the French. Released in 1976, the same year as Mitchell's travels, Tom Robbins' absurdist novel Even Cowgirls Get The Blues followed the giant-thumbed Sissy Hankshaw as she encountered various countercultural avatars, But although just as geographically far-reaching, Mitchell's trip was defiantly insular- the kind of story that hadn't yet been written.

Living between her car and anonymous motels, Mitchell wrote songs on her acoustic guitar since pianos were seldom available. She thought of naming the collection of material "Travelling", but that implied a fixed destination. Instead, she chose a reference to the migration of the prophet Mohammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 AD, which she later summed up as "leaving the dream, no blame".

"'Hejira' was an obscure word, but it said exactly what I wanted," she told Crowe. "Running away, honourably." She continued, referencing her split with Guerin. "It dealt with the leaving of a relationship, but without the sense of failure that accompanied the breakup of my previous relationships. I felt that it was not necessarily anybody's fault. It was a new attitude."2

In a interview with Doug Fischer of the Ottawa Citizen newspaper in 2006, Mitchell touches on the uber-personal reflections of Hejira and her songwriting:

Released 30 years ago this week, the nine songs on Hejira form the remarkable personal journal of a nomadic, romantic dreamer whose aural notebook is filled with the stories of doomed love, late night roadhouse dance floors, wedding gown fantasies, lost chances and a deep yearning to escape and start over.

Mitchell is not convinced Hejira is the best of the 22 albums that made her among the most influential singer-songwriters, male or female, of the past 40 years. She won't attach that label to any of her albums.

'Hejira could only have come from me'

But she concedes Hejira is probably her one album that could not have been made by anyone else.

"I suppose a lot of people could have written a lot of my other songs, but I feel the songs on Hejira could only have come from me," she said an interview with the Citizen.

The stories they tell are so vivid, their observations so naked and the landscapes so haunting that Kris Kristofferson famously urged her in a letter to be "more self-protective ... to save something of yourself from public view."

But Mitchell says self-confession, no matter how risky and revealing, was essential to her writing during that era.

"My songs have always been more autobiographical than most people's," she says. "It pushes you toward honesty. I was just returning to normal from the extremities of a very abnormal mindset when I wrote most of the songs (on Hejira).3

Hejira is a marvel I’m still getting lost in. Joni’s tribute to time spent on the road. Vivid portraits of American iconoclasts seen through her eyes. Her observations through car windows and in hotel rooms. “Furry Sings the Blues” focusses on the redevelopment of Beal Street in Memphis, Tennessee. Her specificity in description and imagery in this album is something to behold. In Toronto, one could sing of the razing of Honest Ed’s a few years back. But Joni’s able to weave an immeasurable and overwhelming amount of nuance into the lyrics that take years to fully comprehend. Each track similarly takes the listener on a journey of human emotional frailty.

I spent my college years on the road, travelling in between classes. I lived by the motto, “No domestic flights.” I travelled from Chicago to Los Angeles and back several times. Chicago to Tennessee, Pittsburgh, southern Utah, New York City. A different rhythm all together from where I sit now, ensconced in domesticity.

A moment reading MFK Fisher in the nook of a Toronto breakfast joint

When you have small children, it often feels like you’re in a cave of echoing screams, high-pitched laughter and guttural crying. An ego-less grappling with sanity. Sometimes, a trip to the mechanic for an oil change is the perfect break you didn’t know you needed. In this case, I visited my mechanic for the yearly (and perhaps overly optimistic) swapping out of winter tires along with an oil change for my vehicle. I dropped the car off at 9:30 am and wandered around the local Kensington Market area waiting for a callback from the mechanic before my car was ready to go. I stopped at a small chic-retro-diner-turned-coffee-shop called Made Rite.

I sat in the nook where you see the blue jacket above and enjoyed my drip coffee and breakfast sandwich while I read MFK Fisher’s Serve it Forth. It was a perfect morning retreat from the mundanity of day-to-day household task execution, and a mental escape from the constant psychological shift that moving house plagues upon you. A particular chapter stood out in Fisher’s first published book, “Pity the Blind in Palate,” which serves as a call to action for this very Substack and hopefully inspires readers to live by the same bon vivant way of being that Fisher unpacks here:

Frederick the Great used to make his own coffee, with much to-do and fuss. For water he used champagne. Then, to make the flavour stronger, he stirred in powdered mustard.

Now to me it seems improbable that Frederick truly liked this brew. I suspect him of bravado. Or perhaps he was taste-blind.

Almost all people are born unconscious of the nuances of flavour. Many die so. Some of these unfortunates are physically deformed, and remain all their lives as truly taste-blind as their brother sufferers are blind to colour. Others never taste because they are stupid, or, more often, because they have never been taught to search for differentiations of flavour.

They like hot coffee, a fried steak with plenty of salt and pepper and meat sauce upon it, a piece of apple pie and a chunk of cheese. They like the feeling of a full stomach. They resemble those myriad souls who say, ‘I don’t know anything about music, but I love a good rousing military band.’

Let the listener to Sousa hear much music. Let him talk to other music listeners. Let him read about music makers.

He will discover the strange note of the oboe, recognize the French horn’s convolutions. Schubert will sing sweetly in his head, and Beethoven sweep through his heart. Then one day he will cry. ‘Bach! By God, I can hear him! I can hear!’

That happens to the tase-blind in just some such way. He eats apple pie, good or bad, because he has always eaten it. Then one day he sees a man turn his back upon the cardboard crust and sodden half-cooked fruit, and eat instead some crisp crackers with his cheese, a crisp apple peeled and sliced ruminatively after the crackers and the yellow cheese. The man looks as if he knew something pleasant, a secret from the taste-blind.

‘I believe I’ll try that. It is - yes, it is good. I wonder —”

And the man who was taste-blind begins to think about eating. Perhaps he talks a little, or reads. All he really need do is experiment.4

Reading this piece of writing helped give me confidence for what I do with this Substack. Each week is an experiment.

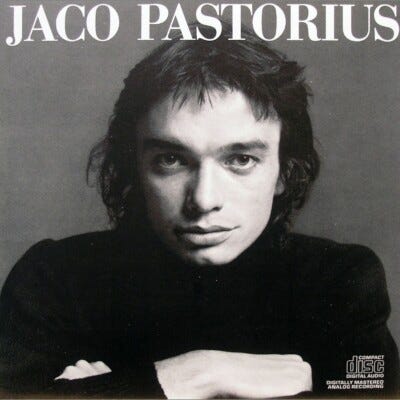

Jaco Pastorius

Joni’s work with Jaco Pastorius on Hejira inspired me to dig into Jaco’s most well-know album, the self-titled Jaco Pastorius (3.5 stars, Penguin Guide), released the same year as Hejira in 1976.

My wife and I painted all three bedrooms of our new apartment this past weekend. We’re still rebuilding our stamina after that whirlwind process. But we bonded listening to the albums’s up-tempo, decadent mix of jazz and orchestral funk, our soundtrack du jour for taping, rolling, and filling in the edges. I was reminded of listening to The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix album for the first time some months ago now, as documented here:

014. Gil Evans - Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix (recorded June, 1974 & April, 1975)

According to the Penguin Guide:

The Jaco Pastorius album is another one that caught me by surprise. I was blown away by the life pulsing though it, too much going on here for simple categorization. From Jaco’s impeccable and unique playing throughout the album but especially on “Portrait of Tracy,” to the epic string arrangements of “Kuru/Speak Like a Child” to Herbie Hancock’s 1970’s piano which can be considered a genre in and of itself, to the steel drums on “Ocus Pocus,” the music constantly pushes forward in an unexpected melange of styles coming together at new angles. The Penguin Guide quips, “Perhaps too many different lineups on show for one record.” I disagree; this is a strength of the record. Yet, the Guide also claims, “[Jaco Pastorius] might stand as Pastorius’s best memorial.”

Jaco Pastorius joined the influential group The Weather Report from 1976-1982. His personal life went dramatically downhill in the mid-1980’s. Wikipedia gives a concise and straightforward account of Jaco’s tragic death in 1987.

On September 11, 1987, Pastorius sneaked onto the stage at a Santana concert at the Sunrise Musical Theater in Sunrise, Florida. Weather Report was an associated act of Santana in the mid-seventies. After being ejected from the premises, he made his way to the Midnight Bottle Club in Wilton Manors.[48] After reportedly kicking in a glass door, having been refused entrance to the club, he became involved in a violent confrontation with Luc Havan, a club employee who was a martial arts expert.[8][49] Pastorius was hospitalized for multiple facial fractures and injuries to his right eye and left arm, and fell into a coma.[50] There were encouraging signs that he would come out of the coma and recover, but they soon faded. A brain hemorrhage a few days later led to brain death. He was taken off life support and died on September 21, 1987,[1][3] at the age of 35, at Broward General Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale.[48] His funeral was held at St. Clement's Catholic Church, Wilton Manors, Florida. Pastorius was buried at Queen of Heaven Cemetery in North Lauderdale, Broward County, Florida.[51]

Havan faced a charge of second-degree murder. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to twenty-two months in prison and five years' probation. After serving four months in prison, he was paroled for good behavior.

The Jaco album given four stars by the Penguin Guide is Punk Jazz: The Jaco Pastorius Anthology (1968-1986):

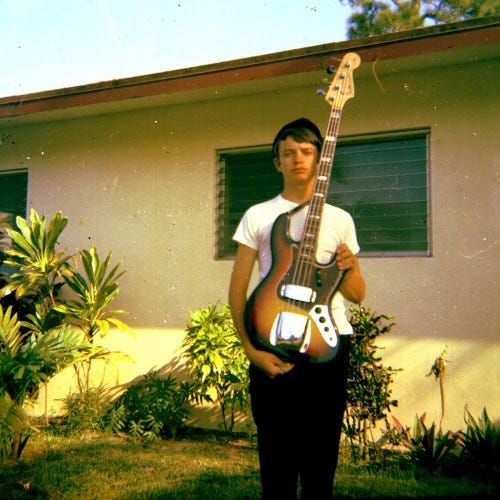

As Jaco Pastorius Inc., run by the late bassist’s children, starts to mop up the bootlegs and unauthorized releases, the contours of their father’s remarkable story becomes clearer. This sumptuous and beautifully mastered set touches all the obvious bases: the stint with the Weather Report (‘Birdland’ inevitably), working with Joni Mitchell (‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’, ‘Dry Cleaner from Des Moines’), Pat Metheny, Paul Bley, and a generous sampling of Jaco’s small groups and big bands with Warners. The real plus, though, is the early material, and for collectors the previously unreleased cuts. We first hear Jaco in his bedroom, playing all the parts - guitar, drums, saxophone, bass - on Pee Wee Ellis’s ‘The Chicken’, a tune that turned up again later in his career; this, though, from 1968 or 1969 when he was still a teenager. We also hear him with Wayne Cochran’s C C Riders with Paul Bley and Pat Metheny from the Improvising Artists’ Jaco. There are later traces with pianist Michel Colombier which may not be known to some listeners. More familiar are ‘Amerika’ (the ultimate electric-bass feature) and the glorious moment on Word of Mouth when Toots Thielemans plays harmonica on Bach’s ‘Chromatic Fantasy’. Poignantly the track listing goes right up to the autumn of 1986, less than a year before Jaco’s pointless death, when he played with Brian Melvin Trio for what was to be the 1990 release Standards Zone, a cover of Joe Henderson’s ‘Out of the Night’ that once again cements Jaco’s jazz credentials.

For anyone who has only heard of Jaco Pastorius, this will be a revelation. For serious collectors, the issue of ‘Okonkole Y Trompa’ from the 1982 tour is a very definite plus, as is that amazing bedroom track. Portrait of the genius as a young man fated not to grow old.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find this compilation album on Spotify or Youtube. But I will now seek it out.

https://jonimitchell.com/library/view.cfm?id=2035

https://jonimitchell.com/library/view.cfm?id=4408

https://jonimitchell.com/library/print.cfm?id=1459

Fisher, M.F.K. (1989) Serve it Forth, North Point Press. pp. 68-69

I haven't listened to a ton of Joni Mitchell, so Hejira is uncharted territory for me. I'm excited to give it a listen!