014. Gil Evans - Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix (recorded June, 1974 & April, 1975)

Exploring the consummate arranger and composer

According to the Penguin Guide:

[Gil Evans] is famously an anagram of Svengali and Gil spent much of his career shaping the sounds and musical philosophies of younger musicians. His association with Miles Davis was definitive of one strain of modern jazz, but Gil went on to rewrite the musical legacy of Jimi Hendrix as well. Born in Canada, and serving a hard-knocks apprenticeship in Claude Thornhill’s band (which also had a big impact on Miles), Gil drew heavily on Duke Ellington as both composer and arranger. His peerless voicings are instantly recognizable.

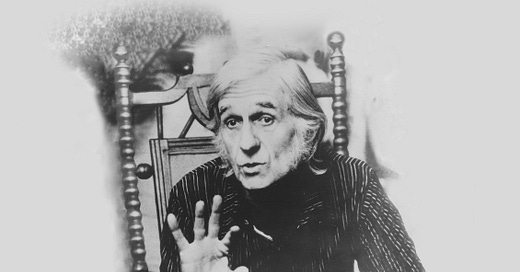

(Side note: Gil Evans looks uncannily like Dr. Brenner in Stranger Things)

Davis and Evans famously collaborated on several iconic jazz classics like Birth of the Cool and Sketches of Spain and Evans is known as a paramount influence on Davis’s evolution.

Miles reserved high praise for Evans:

I used to write and send Gil my scores for evaluation. Gil used to say they were good but cluttered up with too many notes. I used to think you had to use lots of notes and stuff to be writing. Now I’ve learnt enough about writing not to write. I just let Gil write. I give him an outline of what I want and he finishes it. I can even call him up on the phone and tell him what I got in mind, and when I see the score it is exactly what I wanted. Nobody but Gil could think for me that way.1

Gil Evans was a master of his craft; there’s an excellent reddit thread that helps interested parties get a further taste of the man’s music, especially his collaborations with Miles. Penguin Jazz selects the Out of the Cool album, recorded in 1960, as part of the Core Collection:

Out of the Cool is Evan's’s masterpiece under his own name (some might want to claim the accolade for some of his work with Miles) and one of the best examples of jazz orchestration since the early Ellington bands. It’s the soloists - Coles on the eerie ‘Sunken Treasure,’ a lonely-sounding Knepper on ‘Where Flamingoes Fly’ - that immediately catch the ear, but repeated hearings reveal the relaxed sophistication of Evans’s settings, which give a hefty band the immediacy and elasticity of a quintet. Evans’s sense of time allows Coles to double the metre on George Russell’s ‘Stratusphunk,’ which ends palindromatically, with a clever inversion of the opening measures. ‘La Nevada’ is one of his best and most neglected scores, typically built up out of quite simple materials. The sound, already good, has been enhanced by digital transfer, revealing yet more timbral detail.

As a Jimi Hendrix fan, I was more intrigued reading the Penguin Guide blurb for the 1974/75 album, Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix:

A title like that probably did raise eyebrows in 1974. Evans’s championing of Hendrix’s composition - ‘Little Wing’ most immortally - was a controversial but ultimately career-stoking decision. It’s a little difficult to tell, while listening to these powerful tracks, whether the quality of the music is testimony to Hendrix’s genius as a composer or Evans’s as an arranger, or to some strange posthumous communication between the two. Some of the tunes are inevitably moved a long way from source; ‘1983 A Merman I Should Turn to Be’ takes on a new character, as does ‘Up From the Skies',’ two takes of which are included. ‘Little Wing’ remains the touchstone, though, and the recording, from spring 1975, is superb. Now reissued with extra tracks, the Hendrix set is essential listening.

I listened to this album for the first time a couple weeks ago, while I was cooking up black beans from scratch, roasting cauliflower and sautéing mushrooms for family taco night. It was one of my most thrilling musical discoveries in recent memory. Hearing Jimi Hendrix, an artist who blew my mind open to the possibilities of how music could sound, interpreted in this way, was a real treat. Sure, not every track on the album is slamming, but for the majority of the record, I was genuinely grooving out while sautéing the onions with the garlic, adding the mushrooms and glazing them with tequila and soy sauce. The cauliflower was smelling real nice, cooking at 425 in the oven. I was about to make some quesadillas for the kids, shredding cheddar cheese on the box grater while listening to Evans’s arrangements skillfully emulating Jimi shredding on guitar. There was fusion happening on multiple levels, from the music at hand, to my nothing-but-good-vibes association with Jimi Hendrix melding with my burgeoning jazz scholarship, to my use of disparate ingredients thrown together for Taco Tuesday. Funky, slippery, smooth, all-hands-on-deck, transportive, bridging worlds with exceptional intuition and grace. Hendrix and Evans, tacos and out-of-body experiences. Sign me up.

Here’s some context for the album, from a 1974 Rolling Stone article entitled, “Gil Evans: Jazzing Up Jimi:”

Just before Jimi died we were talking about doing a session together,” recalled Evans during a break in recording the Hendrix album in RCA’s studio B. “Alan Douglas [record label and production company boss] was involved with Jimi and came up with the idea of an album where Jimi would just play guitar and have an orchestra built around him – my job. We were to get together on the Monday – after the Friday he died.

Tragic timing.

According to Evans, it was no simple thing to translate the Hendrix guitar artistry into the ensemble form. “The main problem is the inflection, getting that correct, which is something that goes with translating anybody’s songs, not just Jimi’s. Sometimes you have to change the inflection or the rhythmic pattern to make it work for the bigger ensemble. It’s like storytelling. What I do is to try and keep Jimi in mind when arranging. Sometimes I would listen to the record and ignore the sheet music, phrase it the way he did it, although where an individual soloist is involved, you have to let him go his way. But when I wrote out the ensemble passages I would take Jimi’s way into consideration.”

Trying to get inside the mind of Gil Evans here, and the whole process is mind-boggling. How is a work like this created?

About injecting rock into his arrangements, Evans admits: “It’s the contemporary rhythm and sound, to a degree. It’s just automatically incorporated into anybody that works in contemporary music, which I always have. You shouldn’t try to force it but as long as the rhythm and the music fit, it’s OK. The main thing I look for in music is spirit. Living spirit.”

The spirit of Jimi lives on. I listened to the music of the great guitarist on Monday, and was reinvigorated after listening to his version of the “Star Spangled Banner,” which of course stood in stark contrast with the stiff, empty and condescending pseudo patriotism of Trump’s inauguration.

I found a New Yorker article from 2021 which analyzed this performance around the time of Biden’s inauguration:

Jimi’s Woodstock anthem was both an expression of protest at the obscene violence of a wholly unnecessary war and an affirmation of aspects of the American experiment entirely worth fighting for. In “If 6 Was 9,” from his second album, “Axis: Bold As Love,” Hendrix sings that he has his “own world to live through and I ain’t gonna copy you,” finally deciding to “wave my freak flag high,” at which point he unleashes a spastic, flickering, birdlike spray of notes from a guitar soaked in reverb. His rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” turned it into a blazing freak flag, a protective shield for eccentrics, oddballs, weirdos, outsiders, marginal people of every sort. “Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach,” John Stuart Mill wrote, in “On Liberty,” “it is desirable . . . that people should be eccentric. Eccentricity has always abounded when and where strength of character has abounded.” Mill’s use of “character” here should be heard with the emphasis that Dr. King placed upon it, and his warning about tyrannical conformism should be heard as of a piece with Hendrix’s vow that he is not going to copy you.

Rock critic Robert Christgau wrote of Jimi’s Star Spangled Banner in 2019 for the Los Angeles Times:

Jimi Hendrix loved to flash the peace sign, as he did both at Woodstock and on [Dick] Cavett’s show. He loved the counterculture that made him a hero, too. But like most musicians he was more a hippie than a peacenik, much less a radical, known to defend the Vietnam War in conversation back when he started playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” live. His politics were still evolving as of Woodstock and after — most people’s were. And for sure he meant to claim the national anthem for his white, groovy, long-haired, spaced-out tribe. So he tore it down and built it up back up into something so avant and anarchic that peaceniks and radicals have taken it for their own ever since.

That’s because what matters about this “Star-Spangled Banner” isn’t what Hendrix thought it was, if he even knew exactly. Rather it’s what he meant to leave us free to think it was. Thus it’s an image of America that Americans dismayed by what America has become can cherish. Amid the blah blah woof woof of flag-pinned liars and flag-waving know-nothings, it’s a way for those of us who thought America would never have to fight fascism again to remember that we’re doing so to make our beloved nation the land of the free and the home of the brave.

I’ve always had an affinity for the hippie culture, and I think that the movement emphasized the best of aspects of what twentieth-century America could be. Rebelling against, but also naively using the resources, the power, the diversity and the opportunities that being an American citizen inevitably offered. Taking creativity to new heights. I’m proud to be an American because of people like Jimi Hendrix and others whose resistance is informed by living and creating in a society that gives so little to its artists. “Life is pretty depressing without art,” a friend told me on the phone yesterday. And that’s why we listen.

If any readers have suggestions for what they’d like to see more (or less) of with Penguin Jazz A-Z, feel free to message me or comment. I always appreciate feedback, I’m usually better for it. Thanks for reading.

https://jazzviews.net/miles-davis-gil-evans/

Thank you for this piece. I knew from Miles Davis’s autobiography that he and Jimi had tentative plans to record together, but I had no idea Gil and Jimi had firm plans to do so. And I had no idea a Gil-arranges-Jimi album existed.