015. Chet Baker - Let's Get Lost: The Best of Chet Baker Sings (Recorded 02/1953-10/1956)

Examining a way out of the winter doldrums

Look, there’s a lot of bad shit going on. I write to retreat from it all by focusing on jazz, finding solace leafing through the Penguin Guide and spending time with my own thoughts amongst the impending darkness. It’s hard to cope, often times I feel powerless and overwhelmed. Some days of the week, all I want to do is get lost: on a walk in the snow, in my wife’s arms, freestyling over V-tech beats while my children noodle on a kiddy DJ set.

Listen to the news? I get along without it very well. Apply for jobs? But not for me. Cook dinner again? It’s always (food). I sit and listen to Chet Baker. My ideal. I fall in love too easily.

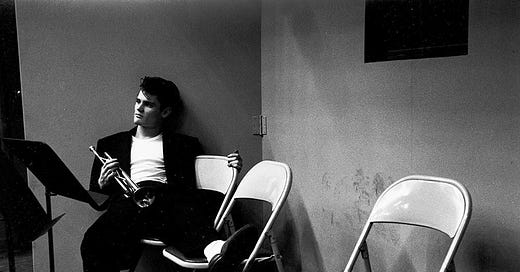

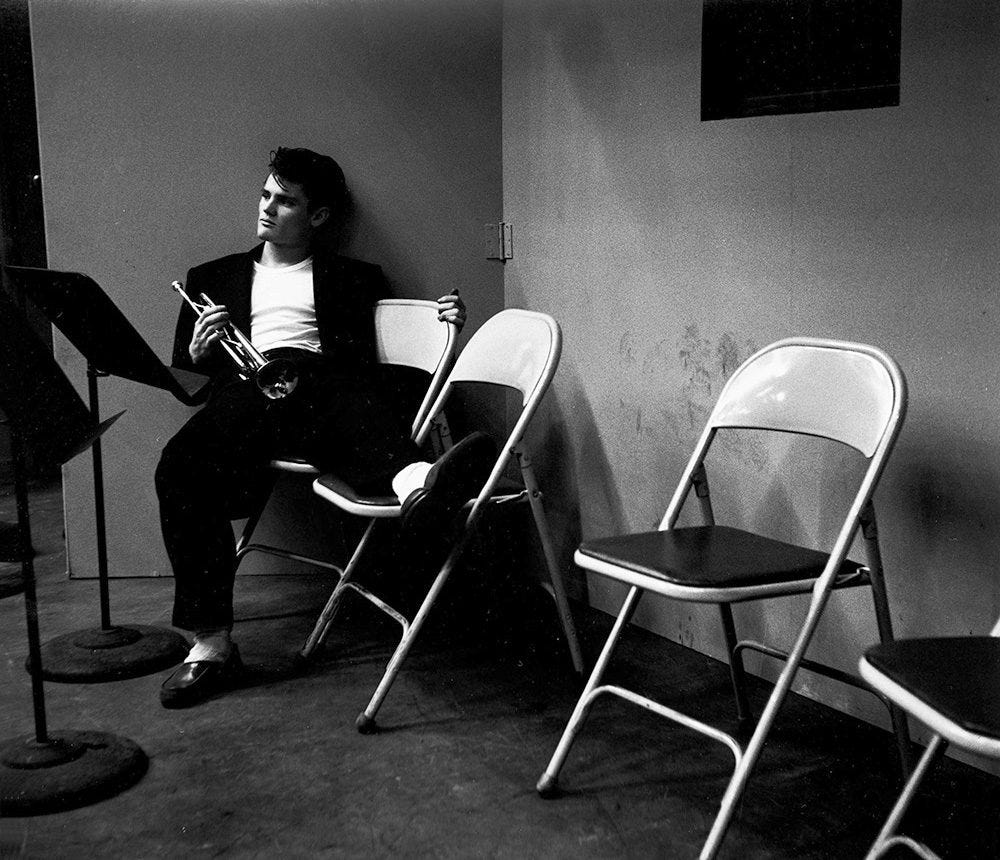

I watched Bruce Weber’s 1988 artful black-and-white documentary on Chet Baker, aptly titled Let’s Get Lost, on the streaming service, Kanopy. The film, also available to watch in full on Youtube (embedded below), is a stylistic, gutter-ball dreamscape, shot all in black and white with noteworthy archival footage of old Italian b-movies that Chet starred in. The editing skillfully juxtaposes many facets of Chet’s life together in an engaging way. Sunshine and Santa Monica palm trees, joyrides with beautiful women and noteworthy jazz history anecdotes stand alongside gut-punch interviews with exes and estranged children. “He was bad, he was trouble, and he was beautiful,” one ex recounts. The myth of the heroic artist brought down to earth by his relationship with drugs and lack of relationship with family. Let’s Get Lost is enjoying a resurgence of sorts. It’s been restored in 4K, and was actually playing at the Revue Cinema here in Toronto this week.

I remember seeing a fictionalized, mostly forgettable portrayal of Chet Baker done by Ethan Hawke, Born to Be Blue (2015), at TIFF. I usually like Ethan Hawke, and I remember there was a Q&A after the film with the actor. But that’s about all I remember. I would have liked to see Harry Dean Stanton play Chet Baker when he was alive. It seems like a perfect pairing, both emaciated wanderers seeking beauty, deeply in touch with nature and life itself. When I think of Harry Dean Stanton, I can’t help but think of David Lynch, rest in peace. Stanton was in five Lynch films, including one of my all-time favourites, The Straight Story (1999). The two were interviewed together for the Harry Dean Stanton documentary, Partly Fiction (2012). Lynch says:

“[Harry’s] got this innocence and naturalness that’s really rare… He says a line, and it’s just real, it’s so phenomenal. And what he does in between the lines is incredible. A lot of people - you can sort of see ‘em, they’re not really listening, they’re not in the thing in between the lines and you can see them start thinking about their next line… just a subtle little thing, not Harry.”

Chet Baker had that elusive quality too, especially, or at least most obviously for me, with his singing. Chet’s singing goes somewhere so definitive and focussed, he’s not thinking about anything else but the lyric at hand; he captures lyrics soft and gentle like, sweet with charm up the wazoo. He’s right there intimately in the moment slowing down time. The nature side of nature vs. nurture.

According to the Penguin Guide:

Baker was the archetypal, some would say stereotypical, ‘young man with a horn,’ brilliant, inward, self-destructive. He grew up in Oklahoma but was in New York to witness the birth of bebop. He played briefly with Charlie Parker and developed a sound that was similar to Miles Davis’s: quiet, restricted in range, and melodic rather than harmonically virtuosic. The famous pianoless quartet with Gerry Mulligan and Chet’s keynote performance of ‘My Funny Valentine’ were important moments in the development of cool jazz. Chet’s heroin habit led not so very indirectly to the loss of his teeth; the film star looks gave way to a sunken and haunted image that was all too easily projected on to the music. However low he sank - and, in later years, Chet was playing only to cover his drug bill - his technique was precise and his range of expression, whether playing trumpet or singing, remained unaffected.

In my Sophomore year at Northwestern, I lived with a roommate who was going through a lot of his own interior emotional battles. I’m not sure it was good for me to live with him, but in hindsight, he was a formative dark cloud presence in my life. He gave me some edge, as I began to hone a fragile self-awareness. That year, I took a film class called Media and Transformation and made an experimental music video featuring Chet Baker’s “My Funny Valentine.”

What I was trying to portray with the piece above was the tightrope walk of white musical artists constructing an identity while appropriating Black musical forms. I was definitely influenced by Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000). Chet Baker’s tragic sense of charm comes from a deep historical well of American fucked-up-ness.

Last week, I found out from a close friend that the sister of a mutual friend of ours had overdosed on fentanyl. She was interviewed on the Youtube channel, Soft White Underbelly, about her story. I won’t share the video out of respect for her and her family. But as I watched the video, my heart broke; I was on the verge of tears, huddled over my computer screen in refuge from life’s unfair barrage of misery.

Another old friend of mine, we’ll call him Lorenzo, ran in the same MacArthur Park circles of Los Angeles. He’d been on and off the streets hooked on various drugs for the past ten years. I hadn’t heard from him in over five years, but last Thursday night, I received an Instagram message from him, “hey bro how’s life.”

Apparently, another childhood friend, god bless him, had gone down to Macarthur Park for a month straight to find Lorenzo, and tried on a daily basis to get him into a treatment program. Thankfully, his tough love efforts were successful, and Lorenzo’s in treatment now, down near San Diego. My friend sent me a photo of the two of them together. It was a relief to see him, smiling looking emaciated but lively.

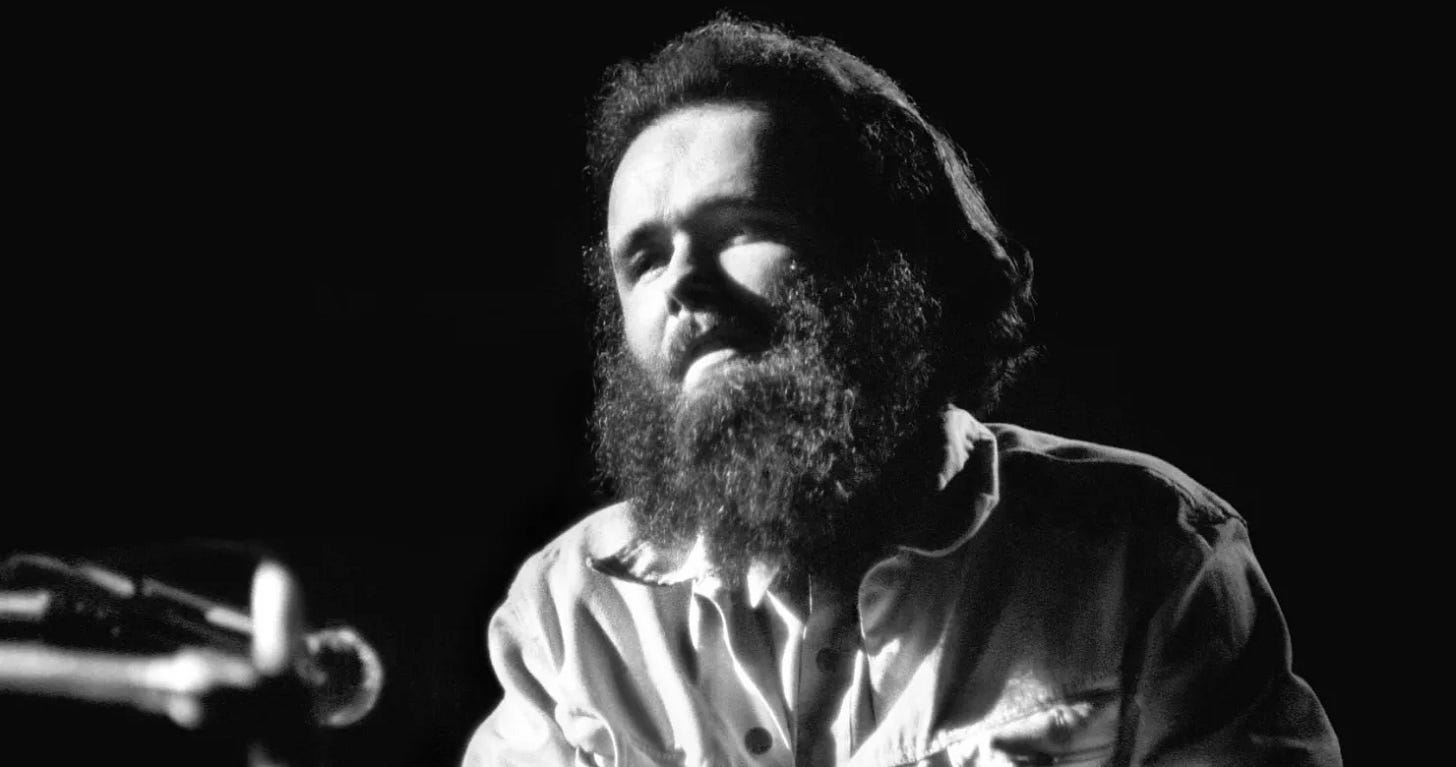

RIP Garth Hudson, multi instrumentalist, unifier and last remaining member of The Band, “perhaps still the group that best embodies the glorious, lawless amalgamation of styles at the very heart of rock and roll.”1 This past Friday night, I did my best to honour the group in the spirit of the times, listening to my vinyl of Stage Fright (1970), the group’s heroine-induced, success-hang-over record.

There are quite a few great tracks on the album, and Garth Hudson’s imposing organ work on the title track is well-known. My favourite track is “All La Glory.” Garth’s work on that track meanders in and out, evoking a carnival funeral atmosphere. Embracing the sorrow of life, but reaching for the stars in the midst of it all. The song contains one of my favourite lyrics of all time:

'Cause to her it's just a fantasy

And to me it's all a mystery

My wife and I listened to the album and toasted the life of our cat, Khaila, recently diagnosed with advanced stage kidney failure. We all have to go sometime.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/postscript/remembering-garth-hudson-the-man-who-transformed-the-band